Horizontal metaphors amidst an archaic landscape

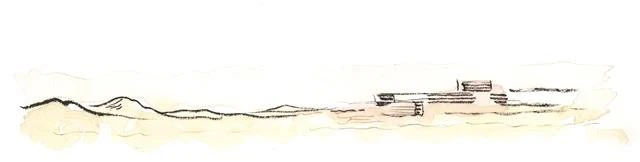

The Maremma, the unspoilt, wild south of Tuscany is a hidden gem. Timeless rural landscapes take your breath away, magic little hill towns of Etruscan origin sit on majestic tufa rocks and fragrant pine woods along the coastline frame endless, sandy beaches. Just the right setting for a holiday house that captures the very essence of this region and translates it into architecture: The House perched on a hilltop.

The beginnings

We are a father and son who run an architecture and design firm, Studio Ponsi. Some years ago – after a careful examination of the financial feasibility, we decided to build a holiday home for our family, either by converting an existing structure or building a new one from scratch. There were just a couple of deal breakers: the site must be no more than a couple of hours from Florence, and as close as possible to the sea.

We spent two years exploring the length and breadth of the Tuscan coast, visiting little apartments with terraces right on the water, villas badly in need of a makeover, farm outbuildings tucked away in secluded valleys, and total ruins. We decided we could not build a new house because of the strict planning rules for buildings close to the water, so we looked a little further inland. We discovered the Maremma region and looked for a vacant plot in a tranquil location with a sea view.

We find the land…

The site we chose belonged to a local real estate agent. It was a field of about half a hectare, tucked away in the hills, close to the two untouched mediaeval villages of Magliano in Toscana and Pereta. It was breathtakingly beautiful, with an uninterrupted view of vineyards, olive groves and rows of cypresses, and with the sea, Monte Argentario and Isola del Giglio in the distance. And it was utterly quiet.

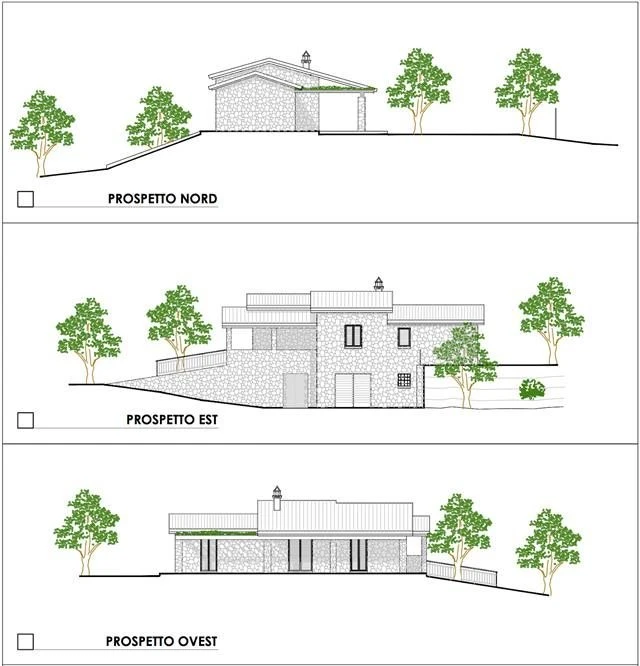

One of the site’s most unusual and desirable features was a purely bureaucratic one: it already had planning permission, and a design for a very traditional building by a local surveyor. This unique opportunity came because of the rules on building in areas of outstanding natural beauty. We asked the local planning department whether we could change the design to suit our more modern tastes. They said yes, so we immediately bought the plot.

A few months later, when the design was almost ready, the building department of the local administration made us an offer. They owned a derelict concrete slaughterhouse in the historic centre of nearby Pereta and wanted to get shot of it. If we bought it at auction and demolished it at our own expense, they would allow us to increase the area of our home by that of the slaughterhouse. We accepted with alacrity.

Plans and ideas

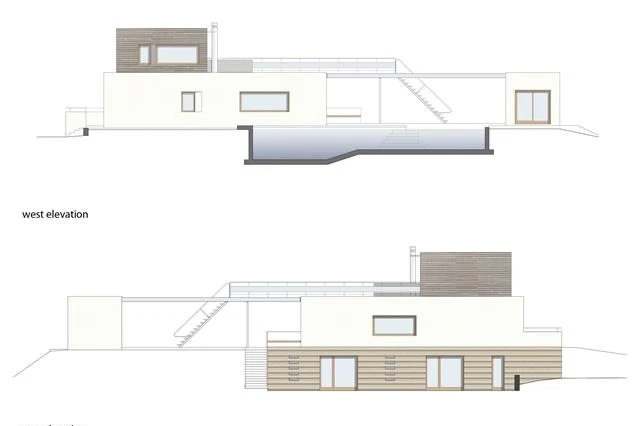

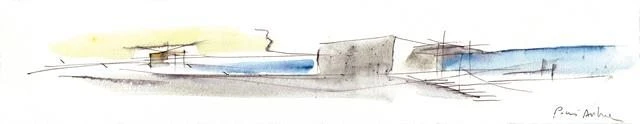

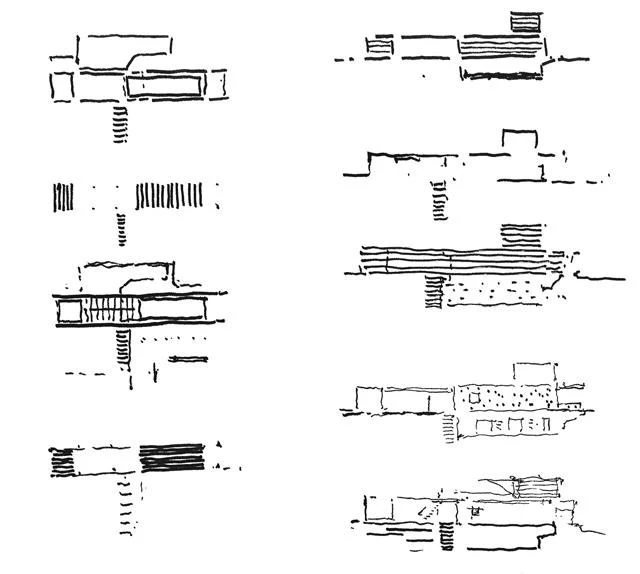

The design obviously had to comply with local rules on things like surface areas, building heights, and excavations, but much of it was the result of observing the surrounding landscape. The lines and volumes of the house reflect the strong horizontals of the hills and the sea.

The terraces, loggias and windows were designed to frame the views, funnel the sea breezes, and create an interplay of light and shadow. Our intention was to capture the dominating horizontals of the landscape and translate them into architectural elements of the house. So we designed a house in three layers, each reflecting one characteristic of the site.

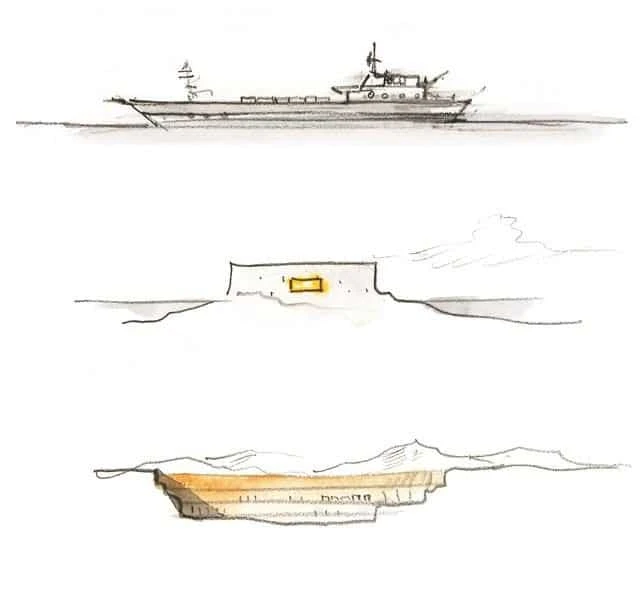

The ground level, clad in blocks of tufa from local quarries, is physically and symbolically rooted in the soil and history of the Maremma. The central floor echoes typical Mediterranean architecture, with flat roofs, white plaster walls and small windows. The upper level is a kind of cabin, covered in wooden boards and emphasising the building’s proximity to the sea, an effect enhanced by nautically themed details such as balusters, flights of steps, and poles.

Construction begins

Once we had completed the drawings and obtained the permits we needed, we contracted out the construction to a local firm with the unlikely name of I Tenebrosi, meaning the tall, dark and handsome guys. The plumber, electrician, parquet installer and metalworker all came from the very civilised little village of Magliano in Toscana.

It was a good choice: they were reliable and conscientious and managed to overcome many unfamiliar challenges. The plumber had a real passion for his work, making some unusual radiators and some tubular steel bannisters; the electrician and the metal fabricator made the galvanised outside lamps and illuminated handrails for the stairs, all to our designs. The deck installer also built a ventilated wall, a first for him.

Two years on, we still believe we made the right decision. We are friends with them all, and they still help us with occasional maintenance.

Geologist or water diviner?

The construction went on for about a year without any particular problems. There was mains water available, but we weren’t allowed to use it to irrigate the garden or fill the swimming pool. When we started work, we brought in a water diviner, who walked around the site with his dowsing rod and declared that there was no underground water.

Two years later, when the building was finished, we decided to review the situation. This time we asked a geologist to find out whether there was an aquifer. He quoted us some €2,000 for a preliminary survey using probes and other instruments, but could not guarantee that there would be water.

We were just about to give him the job, but then the gardener told us about another highly respected diviner who would give us a consultation for a very reasonable €50. We agreed. The next day he got out of his van, took a few steps and pointed at the ground saying, in a throwaway manner, “There’s water right here”. Then he swung a pendulum over the spot, walked a few more paces back and forth, and added, “It’s sixty metres deep”.

We were a bit sceptical, but we decided to believe him. The following week, we brought in a specialist drilling company. Exactly at that point, and sixty metres below the surface, they found a magnificent water source that would give us a well yielding two litres a second.

Landscaping

Having access to water meant we could take a more relaxed attitude towards landscaping and choosing the right plants for the conditions. We designed it ourselves, though we took advice from a local nursery owner.

As you might expect, we are very happy with our house. Although it is not particularly huge, it is big enough for a reasonable number of people, with a variety of private and shared spaces and routes around the building. Just as it has terraces, loggias, steps, and indoor and outdoor spaces for different uses, the pool is divided into specific areas. The “beach” is particularly suitable for children, with only a few centimetres of water; the central section is 1.4 metres deep, and the deepest part lets you swim 15-metre lengths.

The pool reflects the vast sky, which extends from the mountains to the sea’s horizon. The sky and clouds are major features of the landscape, adequately framed by the architecture of the house. The terraces, patios and loggias on three levels provide further vantage points from which to enjoy the beauty of the surroundings as they evolve with the seasons.

Not just a house, but a laboratory

The House is a laboratory, in a constant state of flux as we experiment with new furnishings, finishes, colours, and landscaping. Although it is built to last, we have designed it as a living organism with its own skeleton, skin, and internal organs.

We also like to compare it to a ship, with the hills of the Maremma as the waves. Not literally, because it does not look like an oceangoing vessel, but it does have long straight lines and volumes, wooden bridges, metal staircases and a timber-clad deck cabin, and we never tire of keeping watch over the sky and the islands on the horizon.

Stay at The House perched on a hilltop: Check prices & availability

Travel Guide: Maremma Coast

________________________________________

Text: Andrea and Luca Ponsi, August 2017

All photos and drafts © Studio Ponsi

Article featured in Holiday Architecture Magazine